Written by Mimi Winsberg, MD,

Brightside Health

7 Minute Read

A groundbreaking paper raises the question: Why did so many believe in a chemical imbalance theory of depression?

By Mimi Winsberg, M.D.

In a recent groundbreaking paper in the journal Molecular Psychiatry, authors Joanna Moncreiff and colleagues debunked the theory (or myth) of depression as a chemical imbalance of serotonin, concluding in their meta analysis of related scientific literature: “There is no evidence of a connection between reduced serotonin levels or activity and depression.”

The authors’ main finding is that depression is not the result of abnormalities in brain chemistry, particularly serotonin. And they cite evidence that the “serotonin myth” is not only believed by a large majority of the general public, but propagated by primary care physicians, some mental health practitioners, and much of the media.

The findings have created a stir that is a bit like how I imagine those in the early 16th century reacted when they learned the world is not flat. It is forcing a whole constellation of people to switch their views of what drives people’s moods and actions. It also raises the question: Why did so many believe in a chemical imbalance theory of depression and for so long?

The link between brain chemicals and depression originated in the 1950s when doctors treating tuberculosis patients with Iproniazid observed that patients receiving the drug underwent a sudden and dramatic improvement in their mood symptoms. Separately, in 1954, another group of patients were prescribed the drug Raudixin to treat high blood pressure and they, in turn, experienced a sudden onset of depression; many also became suicidal.

The relationship between drugs that affect neurochemicals and depression came into focus, and the “monoamine” hypothesis of depression was born. The hypothesis postulated that depressive symptoms are mediated through an imbalance of the dopamine, noradrenaline and serotonin systems. Since then, antidepressant drugs have become a mainstay of treatment for depressive disorders, though selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) — medications known under the trade names Prozac, Zoloft and others – did not hit the market until the late 1980s.

Few drugs have generated as much hype as Prozac. One year after FDA approval of the SSRI, 2.5 million prescriptions were issued in the U.S., and by 2008 antidepressants were the third most common drug taken in America. Now, one in six Americans take antidepressants. Yet while we understand some aspects of antidepressants’ effects, many uncertainties remain.

What has been certain for well over a decade is that the monoamine theory of depression is oversimplified at best. If researchers had to sum up the relationship of serotonin to depressive symptoms, the answer would be “it’s complicated.” And the question of how serotonin levels relate to depressive symptoms is a separate question from whether SSRIs actually help alleviate symptoms of depression. (In many instances, they do.)

In fact, as the Molecular Psychiatry umbrella paper suggests, some changes in serotonin levels in depressed patients may be compensatory adaptations to antidepressants. So even though an initial likely effect of an SSRI is to make more serotonin available, in the long term, the brain and body may adapt to the SSRI by downregulating serotonin receptors and function.

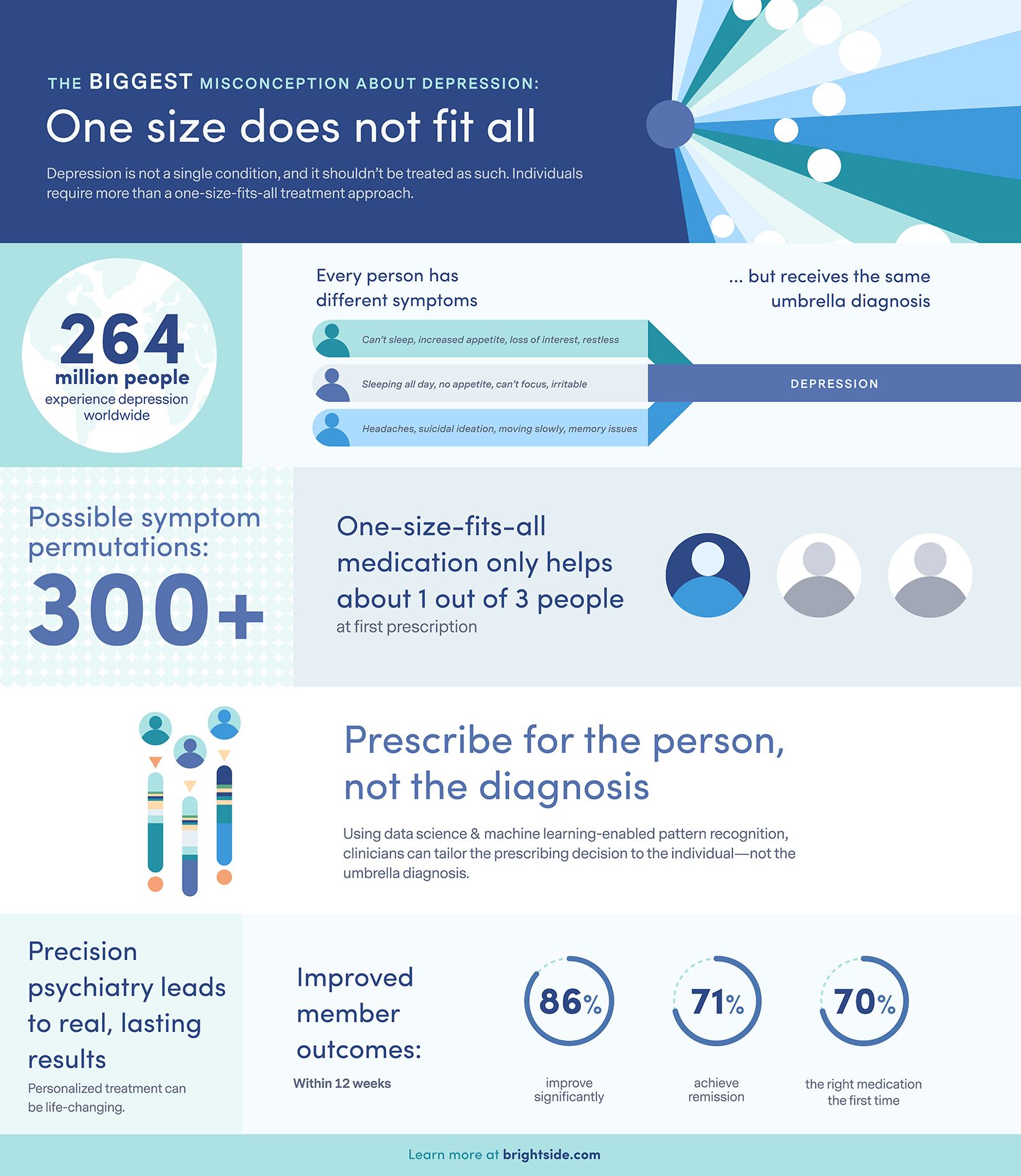

What do we understand about depression? A few things, as it turns out. Like the Molecular Psychiatry umbrella paper, it’s an “umbrella” diagnosis. Under the umbrella label of depression, patients can present – or appear – in a large variety of ways with myriad symptoms. It’s what we call a “heterogenous” diagnosis.

To qualify for the diagnosis, people must have one of two primary symptoms (depressed mood, or inability to enjoy activities that would otherwise bring pleasure) and at least five out of nine total symptoms. Many of these symptoms are bivalent – meaning they can present as one of two extremes. So a symptom of disrupted sleep might mean trouble falling asleep, or sleeping too much. Same is true for appetite.

Tally the number of symptom permutations one can have and still be diagnosed as “depressed,” and we arrive well over 300! Two patients might both be depressed and look nothing alike, with one patient nervously pacing, unable to eat or sleep and considering suicide; and another overeating, sleeping too much, feeling tired with little energy, and unable to concentrate. The brain chemistry patterns of these two patients are likely different.

At Brightside, we consider the particular symptom pattern that each patient presents with, and we take a precision approach to treatment. One increasing advantage of online therapy is that it is technology-enabled and can draw on and produce data to generate key insights about treatment. A psychiatrist’s key responsibility is to determine whether to prescribe medication, and if so which medication. With the application of data science and machine learning enabled pattern recognition, we help our doctors tailor their prescribing decisions to the individual and not to an umbrella diagnosis – a practice we refer to as precision prescribing.

The widespread misconception of depression as a chemical imbalance may be less of a problem than the misconception of depression as a single disease, along with the prevalence of one-size-fits-all prescribing practices, in which millions of patients are prescribed an SSRI that may be suboptimal for their symptom presentation. For some patients with some symptoms, serotonin activity may play an important role. That role may be less about increasing available serotonin and more about stimulating the formation of new brain cells that use serotonin to communicate with one another.

Because the Molecular Psychiatry review paper has put all of depression under one umbrella as if it is a single disorder, it is not surprising that no simple and uniform biological findings emerge – and no obvious “solutions.” No reputable psychiatrist would ever have recently suggested that a heterogeneous condition like depression be attributed strictly to a deficit of serotonin, yet the paper has sparked articles in the mainstream press that uniformly decry the use of SSRIs and lots of “I told you so” chatter on social media.

We must be careful in our understanding of this paper, which did not look into the effectiveness of antidepressants, but sought instead to uncover serotonin changes in depression. It’s the equivalent of studying all people who have a problem with their legs and classifying them with a walking disorder. Depending on the cause of the disability, underlying biology and effective treatment might vary.

But what’s interesting about Dr. Moncreiff and colleagues’ work is that it may propel a step forward in the understanding and treatment of depression. It will challenge the primary care physicians and therapists who utter the words “You have a brain chemical imbalance” and suggest an SSRI without consideration or further analysis of specific symptoms.

Indeed, we are on the forefront of a better understanding of biological as well as psychosocial models of depressive symptoms. Brain scans and tissue studies have shown that chronic and repeated stress and major depression are associated with changes in the brain, such as loss of connection between neurons. Some of these changes can be seen as a loss of brain volume in key areas of the brain involved in mood regulation.

Whether mediated by antidepressants or therapy, the path to healing likely involves enhancing synaptic connections between brain cells. With the advances of science and technology, I believe we may witness not just breakthrough technologies to treat depression but breakthrough understandings that come from the implementation of these treatments.

Interested in learning more about how Brightside Health can help you offer life-changing mental health care, including for the most severe cases? Visit us at www.brightside.com/partnerships, or reach out directly at [email protected].

Originally published in The San Francisco Examiner

Get in Touch